Hosting a hacker and maker conference in the middle of a field is an interesting concept; providing high-speed fibre-optic network capabilities to attendees’ tents pushes it from interesting to fascinating; and if that challenge weren’t enough, add in providing a local GSM network, supporting calls both locally and out to the wider world, and the whole thing sounds impossible. That, though, is Electromagnetic Field, or EMF Camp, a three-day making-and-camping festival held in the UK every two years.

“EMF was started as a weekend of friends going camping and got wildly out of hand,” explains co-founder Jonty Wareing of the event’s origins. “In 2009 Russ and I had founded London Hackspace and the Hackspace Foundation, and by 2012 there were Hackspaces popping up all over the UK.

“We originally set out to have a weekend camping together with some other Hackspace friends, but eventually ended up aiming to build something more akin to the Chaos Communication Camp in Germany. We had talks, workshops, 300Mb internet via a 5km microwave link, a bar, electronic badges, and approximately 400 attendees. We aim to build an extremely diverse event that brings together people across many disciplines to exchange knowledge and discover new interests – if you have an inquisitive mind or an interest in making things, you’ll feel at home.”

“I got to find out about EMF a few years ago,” Sam Machin, former telecommunications engineer for Orange, O2, and current API developer for Nexmo, recalls. “2013 was the first one I went to, which was a one-day event; 2014 was the first Camp. We actually did build a very basic, small GSM test network in 2014 at EMF: we had two base stations, and I think it was just a small experiment, it wasn’t a camp-wide thing or anything like that.”

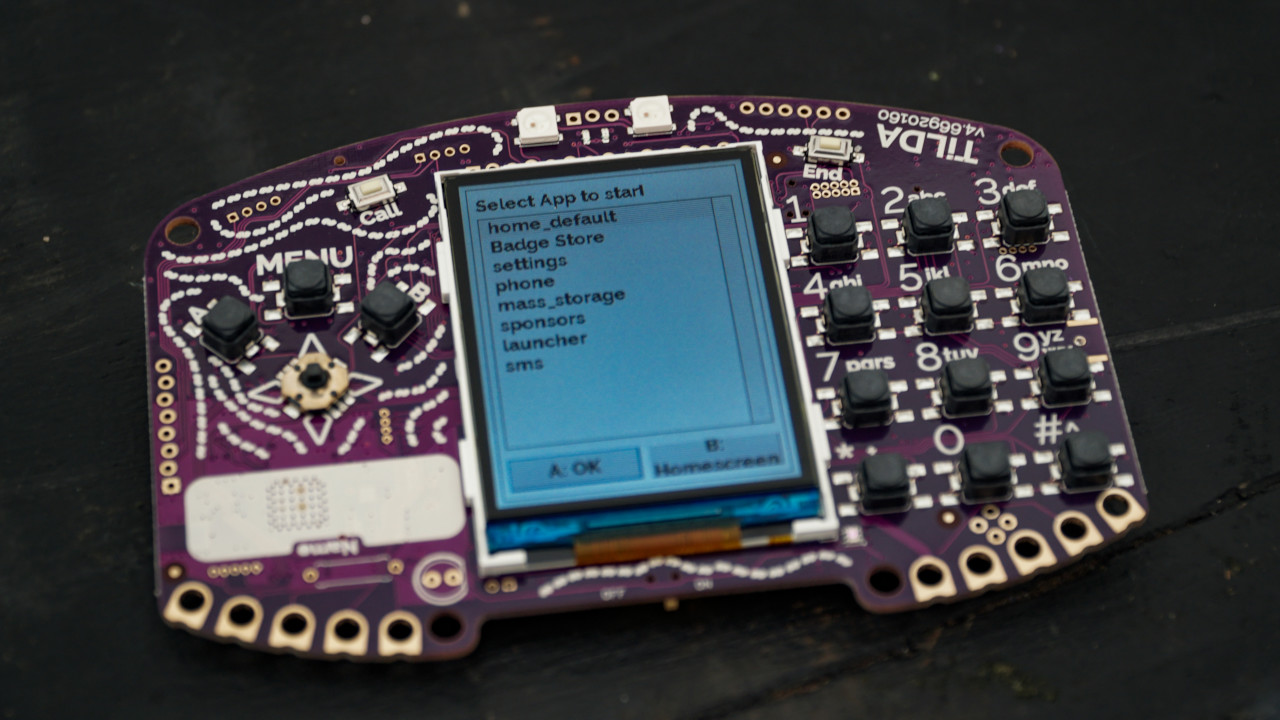

#BadgeLife

The idea to build on this prototypical, small-scale network centred around one thing: the event badge. “There are all these kind of embedded microcontroller badges,” Machin explains. “Basically, if you search for the hashtag #BadgeLife, it’s become known as, there are a couple of really interesting articles on the whole thing. The big thing that they wanted me to do for the EMF badge this year was to put GSM on the badge. It’s kind of always been working towards the idea of being a phone or a communications device. 2016, actually, I did a project which was I put SMS on the badge but via Wi-Fi, so we gave every badge a virtual phone number and delivered SMS to and from that number to the badge.

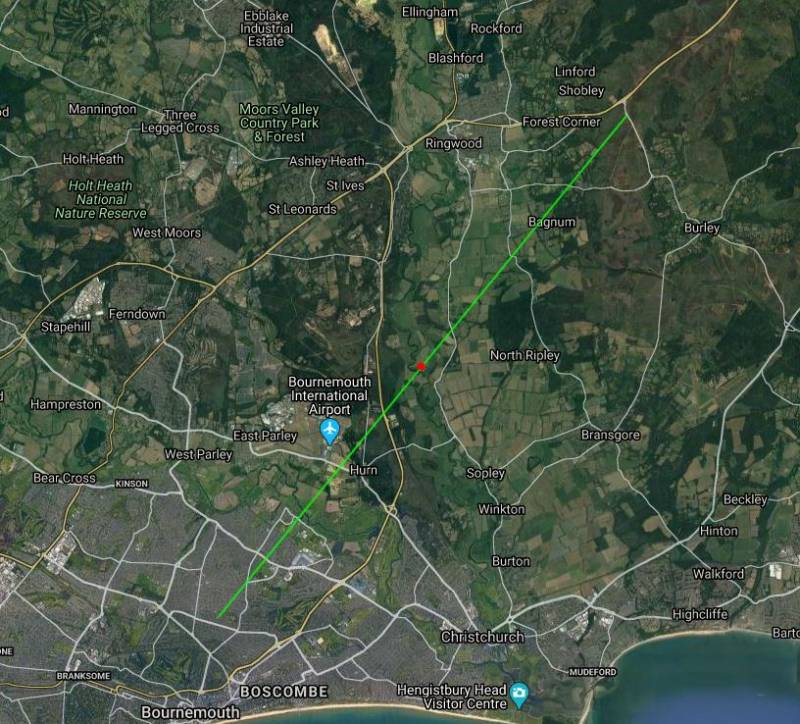

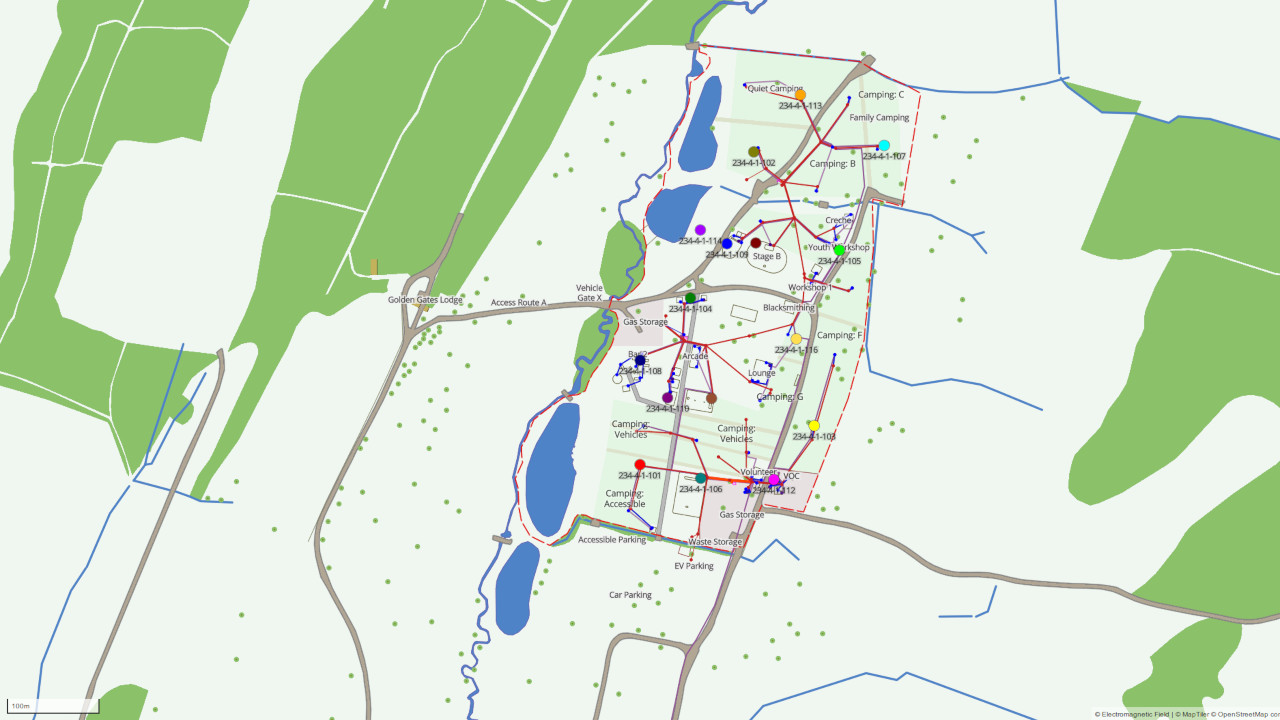

“We were aiming at sort of 2,000-odd badges to hand out, so quite a lot of devices, and these badges are very… prototype-y, if you know what I mean. They’re not a very finished product: the firmware was still being written for them the night before. We didn’t actually give them out until the Saturday because we were still debugging stuff. Also, the site we were using this year at Eastnor [Herefordshire] had very poor mobile coverage anyway, it was in a kind of valley. We weren’t really in the middle of nowhere, but we were definitely in a not-spot, so to speak.”

Roll-Your-Own Network

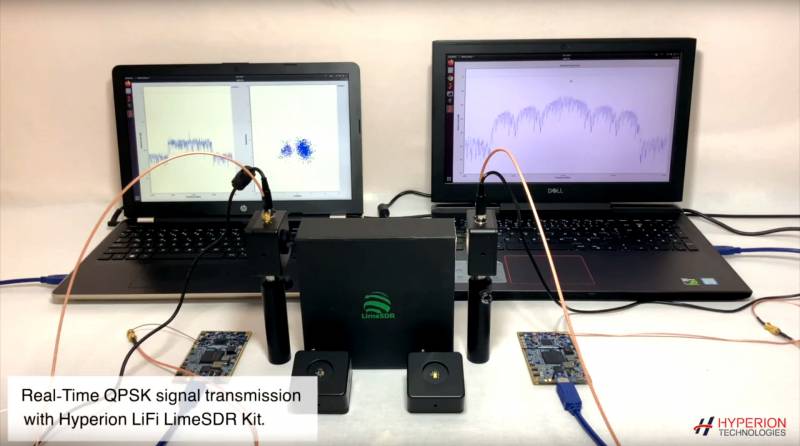

The idea of a site-wide GSM network, to support both the badges and attendees’ own devices, was quickly raised. “Jonty had this idea that ‘hey, if we’re going to put GSM [on the badge] we need a GSM network,’ and obviously he knows the sort of stuff I have a background in, and also I have a background in building hacky projects and sponsoring stuff,” Machin recalls. “He’d already had contact with Lime, [and] I ended up taking on that project to sort of fill in the gaps, basically.”

“We actually approached Lime in 2016 when EMF was based in Guildford, just down the road from the event – they’d just pushed the Crowd Supply [campaign] for the original LimeSDR, and we were very interested in having them along to the event. Unfortunately, we couldn’t make it work that year,” explains Wareing. “Cut to 2018 and we were beginning to assess the feasibility of a GSM network at EMF so we reached out to everybody we could think of who might be able to help, and Andrew Back was suggested. I dropped him an email mentioning that we were considering using Lime equipment to run the GSM network as it was both cheap and would work well – little did I know that he was actually working for Lime!”

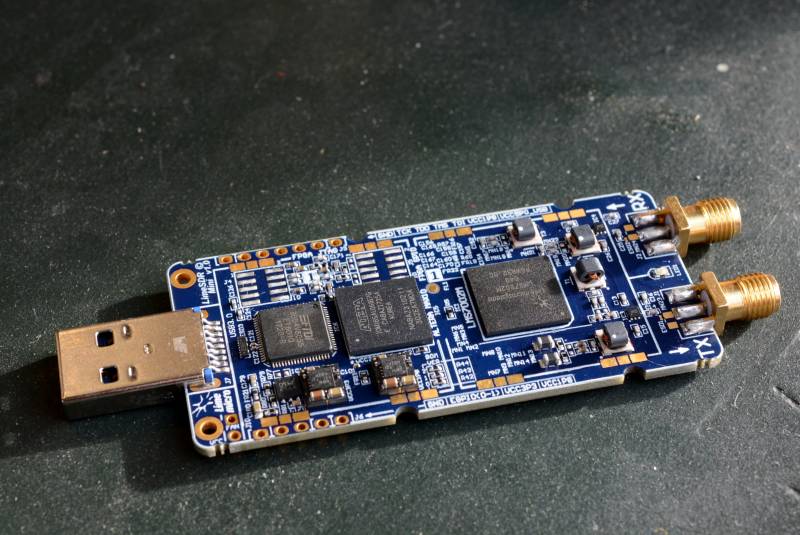

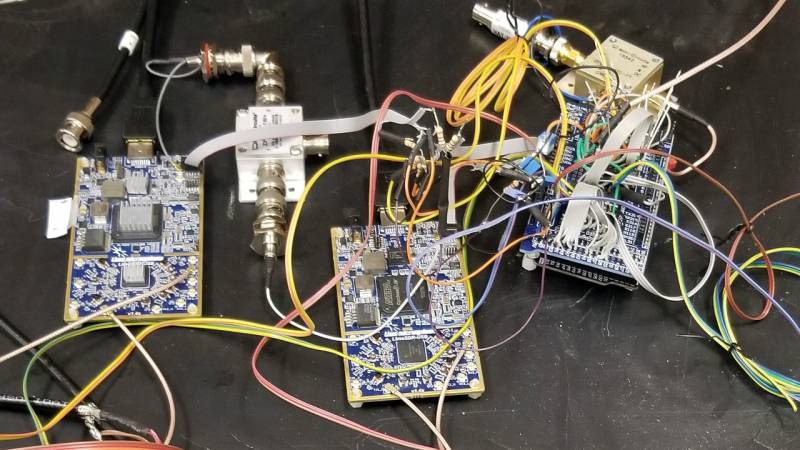

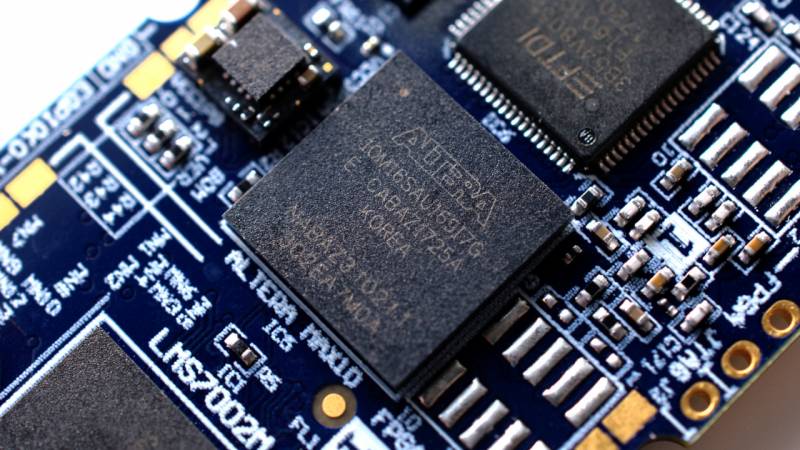

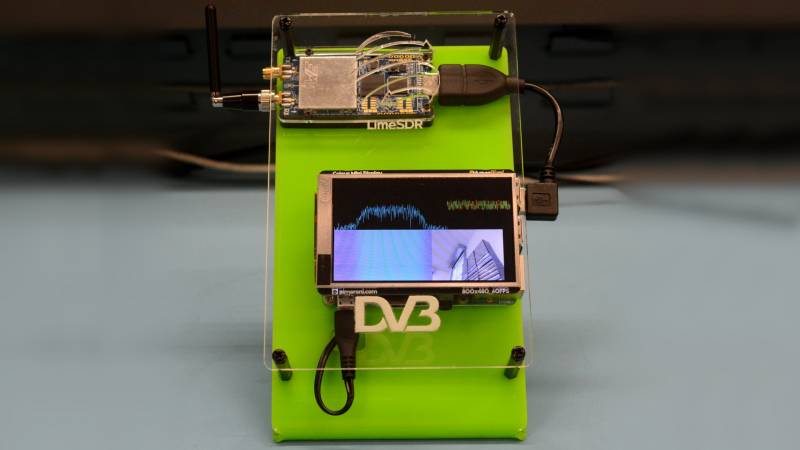

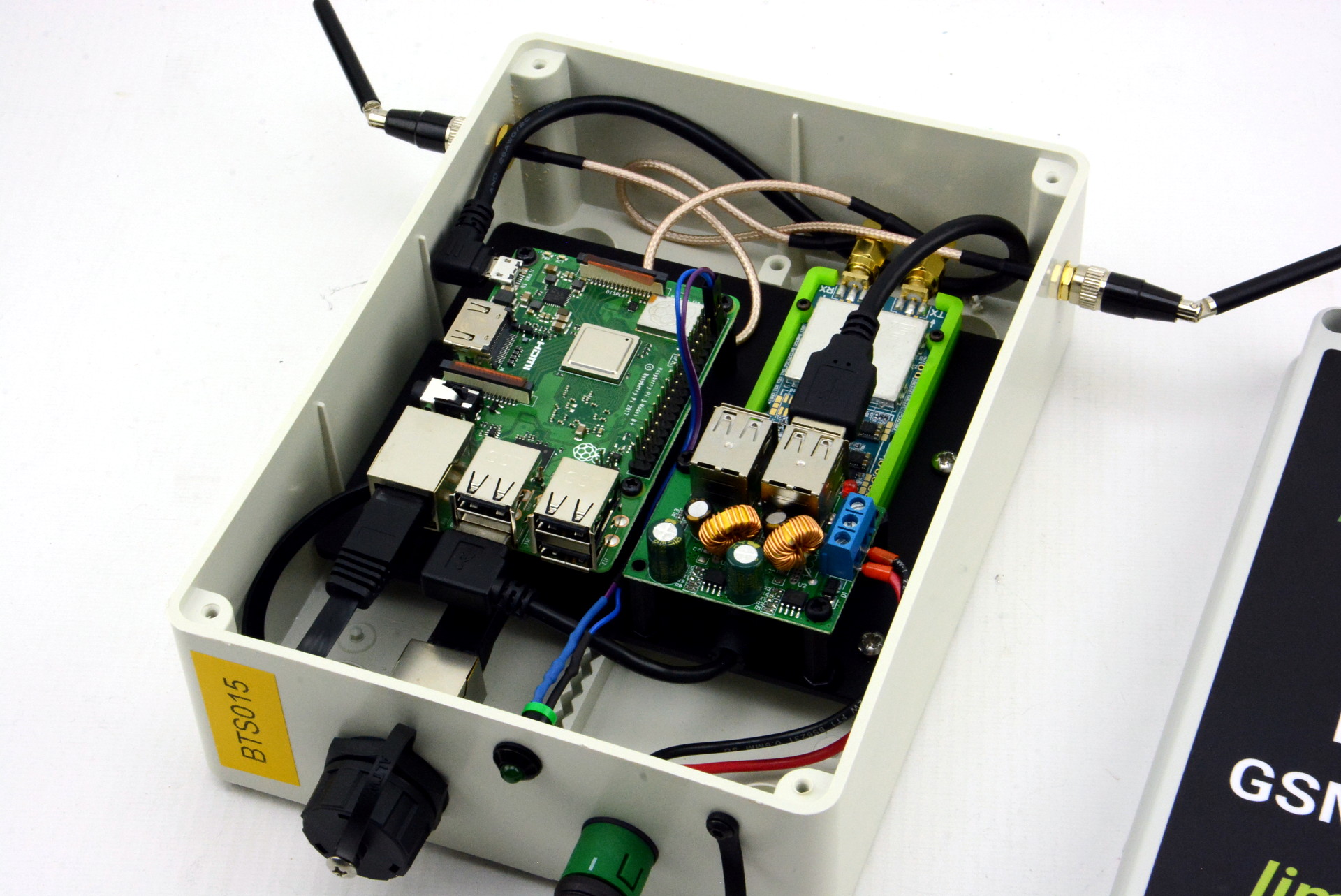

“Access to radio spectrum wasn’t confirmed until a few weeks before the event, leaving us very little time to put together a solution. However, using off-the-shelf components such as the LimeSDR Mini and Raspberry Pi 3 Model B+, we were able to assemble a total of sixteen self-contained base stations — complete with suitably ingress protection (IP) rated enclosures and fittings — in a matter of days and at a very low cost,” explains Lime Microsystems’ Andrew Back. “While the end result was a tactical solution and perhaps not something that you would roll out in a production network, it has served to demonstrate very clearly the power of low cost, high performance SDR hardware, when combined with commodity compute and open source stacks.”

“Lime was really helpful from the hardware side of things,” Machin adds. “I was initially a little bit sceptical of if the Pi was up to running GSM, because certainly previously you need a reasonable amount of processing power. I think the Pi 3 has sort of crossed the boundary, and it’s a bit of a combination, I think, of the open-source software radio stuff getting more and more efficient and the computing power is ramping up. We’ve hit a sort of inflection point in optimised software and more powerful CPUs.”

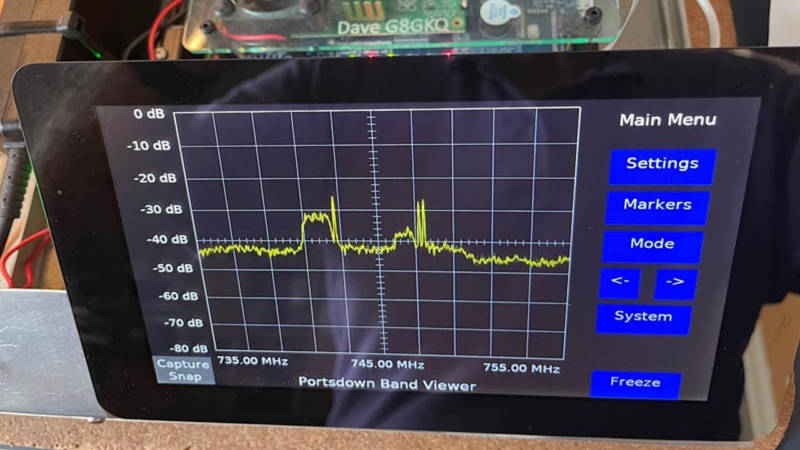

Size and Power

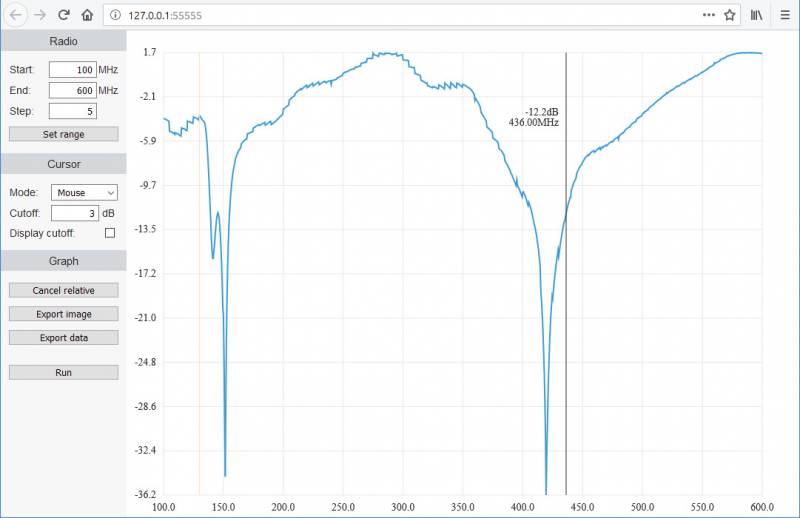

The Raspberry Pi solved half the hardware equation, but it was the open hardware LimeSDR Mini that solved the other: providing affordable software-defined RF in a small, low-power form factor. Combined, the two devices form a system far smaller than a traditional GSM base station – and that, Machin explains, is key. “Because the RF side of the Lime[SDR] is low-power transmit, you don’t want to have long antenna cables. In traditional GSM engineering you would put your base station in a cabinet at the bottom of the mast and then you’d run your co-ax cable up to your antenna at the top of the mast, but the losses you’d get on doing that with the SDR, of running a long co-ax cable, would be significant. You’d lose so much of your power just getting up the mast. What we’re now doing with low power, we’re actually putting the entire base station unit on the mast so that the distance between the RF unit and the antenna is maybe an inch of cable. It’s a very small pig-tail connector.”

The combination of Raspberry Pi and LimeSDR Mini brings with it another major advantage: cost. “The network we built in 2014 was using a software defined radio and a compute unit, but I think there, even for the cheap ones, we were looking at $1,500 for each base station. So, in four years we’ve come down probably eightfold in cost, and complexity and power and all the other stuff that goes with that, because stuff’s got physically smaller as well as cheaper.”

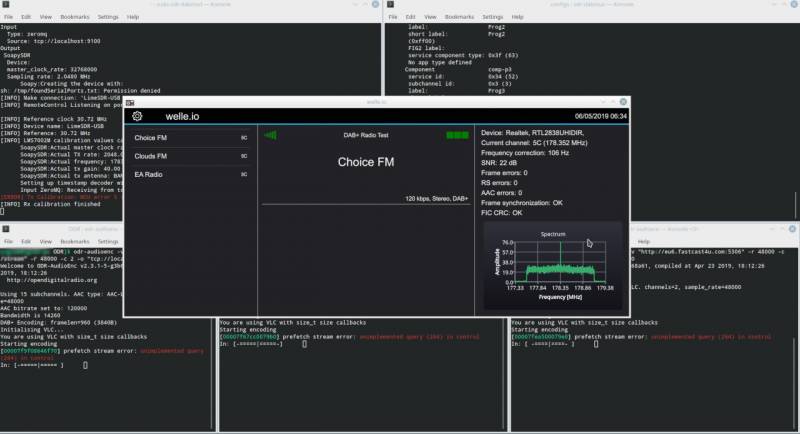

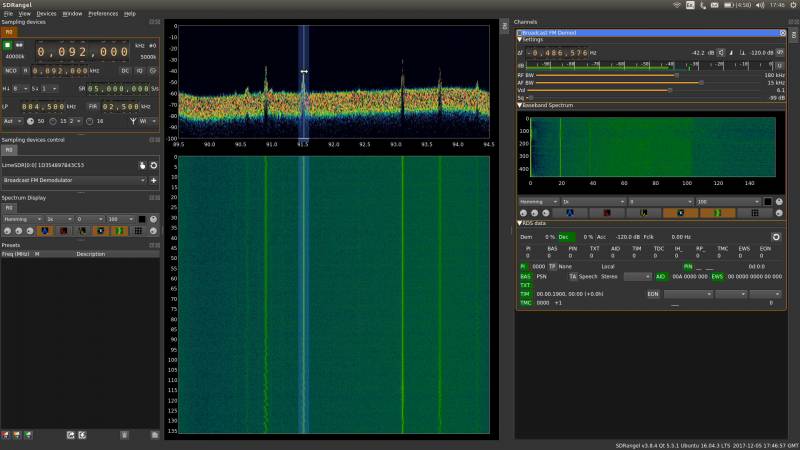

The Software Stack

Hardware is only half the story, though: the best software defined radio in the world is nothing without software to define it. “The GSM system is something called Osmocom [Cellular Network Infrastructure], which is the open source mobile communications stack. What’s nice about that one versus the OpenBTS stuff I used previously is Osmocom is trying to recreate in software all the logical components of a mobile network. So, anybody who’s worked in mobile carriers will be able to recognise terms like BTS, BSC, MSC, HLR, SMSC, a whole bunch of acronyms usually ending in C, and these are all logical elements in a GSM network,” Machin explains. “Osmocom produces software equivalents of those, which makes it quite easy to understand as someone who’s in that [field of work]. The OpenBTS project is a lot more about condensing all of that and basically providing a GSM radio on one side and a SIP phone on the other. It’s like a way of turning a GSM into a PBX. Osmocom is more like a real mobile network.

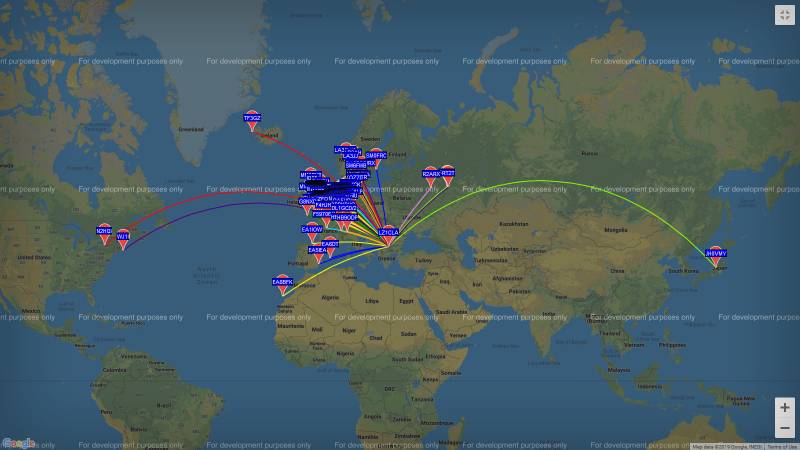

“I worked with a team called EVENTPHONE. They’re a German group who do DECT networks for events like this, so they’ve got a whole bunch of DECT base stations and provide DECT coverage. People bring their home phones, which is quite funny. They build a Voice over IP network core and managing numbers and stuff, and we built it as a combined network that provided both DECT and GSM and regular SIP for like desk phones around the site, all on one numbering plan and things. Osmocom Network In A Box on its own just allows calls between the GSM devices, but in order to integrate this with both the wider DECT and SIP networks and to go out to the PSTN, we needed to connect up using their Osmocom-SIP connector, which then allowed us to send all our traffic into a combination of Asterisk and Yate. It was a Voice over IP core network, so much like a large office corporate system or something, which then had interconnection out to the real phone network through Nexmo.

“We ran all the base stations over VPN connections back to the core network, because of course it was running over the IP network, the Ethernet network, that we had across the camp. We had to think about how we were doing that because it was over a public network and we didn’t necessarily… You know, it’s a hacker camp, you don’t want people sort of managing to poke at your base station and things! [Laughs]”

Future Deployments

The potential of low-cost, low-power easily-deployed GSM base stations powered by open-source software goes beyond providing coverage at hacker camps. “What I think is interesting is the software is at the stage now where non-telco-specific developers, the kind of person who is running their own email server, could probably run their own GSM network at home, on a small scale. If you want to run a single cell then that’s definitely well within the grasp of somebody, to download the Osmocom packages, install them, follow the docs, and kind of do the basic configuration, and plug an SDR in, and you can have a GSM network in your apartment. It’s only when you start to think about spreading this out across multiple areas or serving more users that it’s where a little bit more of the complexity comes in. It’s probably a very good analogy to an email server: running an email server for your own email service, maybe for you and your family, is quite easy, running an email [server] for a medium-size group of users across a company or something requires a little bit more skill. But it’s definitely becoming a more commoditised technology, rather than a specialist technology.”

Machin has given thought to areas where the same core concepts could be deployed for social good, too. “There’s a lot of push for rural broadband connectivity, you know, these fibre projects and rolling out VDSL, even. What we’re finding now is there are plenty of villages which have got excellent broadband coverage and no mobile signal, ironically,” he explains. “For young people, that’s fine because you say ‘I’ll just use Wi-Fi,’ then they’ll use WhatsApp. When they’re in the village their [cellular] phone doesn’t work, but that provides a service they don’t need because everything’s on IP. But, equally, GSM can work for visitors and people coming into an area, or people who just want to use basic phones, you know, dumbphones, and the older generations.

“The challenge with disaster recovery, in terms of providing a service to general population, would be in that transmission level, but of course if the broadband network is still working then potentially you could do something. Providing quick plug-and-play private GSM networks for first responders or disaster recovery, that kind of stuff. One interesting one would be the idea of something like a Rest Centre, so if you have an evacuation of people you could provide coverage there. You could say ‘hey, we’re going to evacuate,’ so you take something like hurricanes in the US where they evacuate a whole bunch of people, now you’ve got one area you can say ‘well, actually, yes, we are going to build a phone network here, we’re going to drop a whole bunch of these base stations around the Rest Centre, around the hall or whatever stadium you’ve put people in, and we’ve got maybe a satellite link or something to tie this back into the rest of the world.'”

Added a ridiculous antenna to the #emfcamp badge, because why not… pic.twitter.com/8B6G6iSrMR

— Matthew Harrold (@MatthewHarrold) September 13, 2018

“This was a fun project to work on and we’re delighted to have been able to support EMF Camp,” Back concludes. “We’re looking forward to its return in 2020, and there has already been much excited discussion about how we can build on the success of the 2018 network to create a more much ambitious wireless infrastructure for use by attendees and in workshops.”